Close

MOANA

This series of black-and-white images are the work of James McDonald, who as well as being a photographer and film-maker, was also an artist and occasional museum director.

Here’s Megan again.

MEGAN

I love these photographs because they activate the hīnaki [eel traps] in a way, by showing how they were used, how they were made – showing them as part of the culture, not separate from it.

MOANA

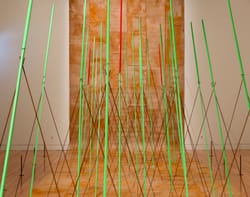

The photos to your right are from the Whanganui River. The ones further to the left are from the Waiapu River.

Look closely at these photographs. You can see craftspeople at work on half-finished hīnaki. We can also see how these traps are placed and anchored in the flow of the awa [river].

These images also capture a who’s who of museum and ethnographic talent, including Elsdon Best and Sir Āpirana Ngata: people who were passionate about the revitalisation of Māori art and cultural practice through making or doing.

Ngāti Mutunga scholar Te Rangi Hīroa, also known as Peter Buck, was a key contributor to the expeditions. You can see him in the photographs, smoking a cigarette in the water.

Te Rangi Hīroa was one of the first Māori anthropologists, and later he became director of the Bishop Museum in Hawai‘i. He was fascinated by fishing, weaving, and netting. He was central to these expeditions, and supposedly directed the photography.

Te Rangi Hīroa’s scholarship is still used today. His hands-on approach to his research remains inspiring.

MEGAN

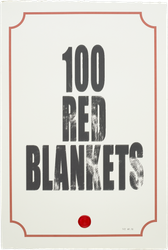

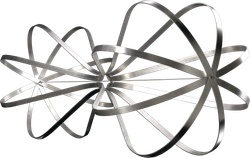

One of his methodologies was that you had to know how to make what you were looking at first, as part of the recording. So he’s learning about hīnaki by making them – a bit like Matthew McIntyre-Wilson and his silver and copper hīnaki.

Matthew is doing a lot of work with iwi [tribes] up the Whanganui River related to hīnaki, so there’s a connection there between these images and his art work.

MOANA

And there are more whakapapa [genealogy] connections through these awa. Let’s continue on to Natalie Robertson’s photographs of the Waiapu River.